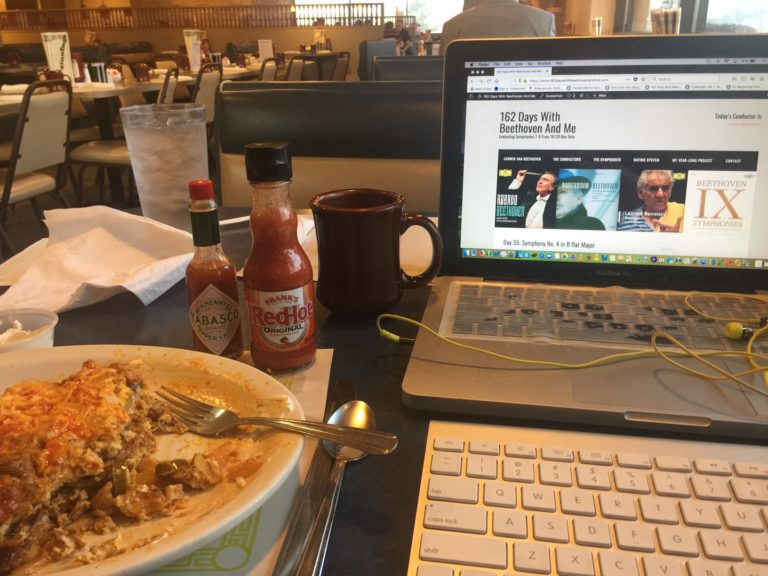

I think I’m addicted to Mexican chicken omelettes (with plenty of hot sauce) from New Beginnings restaurant.

Or, maybe, I simply like restaurants where I can just sit, without being bothered too much, and have endless cups of coffee poured for me while I work. Some restaurants in town are unsuitable for that – for me, anyway. I have too many friends and acquaintances in certain restaurants. I can’t eat breakfast there without being talked to far more often than I’d like.

If it weren’t for my arthritic knee, I’d probably have remained at this restaurant all morning. As it is, I had to leave because there mere act of siting in the booth was giving me excruciating pain. I had to stand and walk around every 15 minutes or so, and that was getting embarrassing. So I left.

Being home was no picnic, either, though. But at least here I can put a bag of frozen vegetables on my knee to help ease the pain.

Which is what I did.

So, that’s what I’m doing now: sitting with a bag of frozen mixed vegetables on my knee while I listen to Argentine conductor Daniel Barenboim (1942- ) conduct Staatskapelle Berlin as that noteworthy orchestra plays Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in B flat Major.

So, that’s what I’m doing now: sitting with a bag of frozen mixed vegetables on my knee while I listen to Argentine conductor Daniel Barenboim (1942- ) conduct Staatskapelle Berlin as that noteworthy orchestra plays Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in B flat Major.

In addition, I’m watching a hummingbird sample a few flowers on the balcony.

Life is good.

Except for these damn knees.

Anyway, I experienced Maestro Barenboim three times previously in this Beethoven project of mine:

Day 2, rating: not “Meh” but not “Huzzah!”

Day 20., rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 38, rating: not “Meh!’ but not “Huzzah!”

I always find Barenboim to be solid and dependable. So far, I can recommend this CD box set from Warner Classics, even though I haven’t always thought the performances warranted a “Huzzah!” rating.

Let’s see what today brings.

But first, let’s look at the excellent liner notes, written by Robin Golding:

The work’s basically cheerful and occasionally charming character may perhaps be a reflection ofr Beethoven’s love of Josephine Brunsvik, whom a number of writers have identified as Beethoven’s mysterious “immortal beloved.” She later married a count, but at the time that he was working on the symphony, there is no doubt that Beethoven fondly hoped that she might marry him.

That’s an interesting historical tidbit. Yet, I wonder how Beethoven went from what appears to be sadness, perhaps even heartbreak, to creating something so upbeat, bouncy, and fun – or, to use Golding’s words, “cheerful”?

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 4 in B flat Major), from this particular conductor (Barenboim, at age 57) and this particular orchestra (Staatskapelle Berlin), at this particular time in history (May – July 1999) on this particular record label (Warner Classics) is as follows:

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 4 in B flat Major), from this particular conductor (Barenboim, at age 57) and this particular orchestra (Staatskapelle Berlin), at this particular time in history (May – July 1999) on this particular record label (Warner Classics) is as follows:

I. Adagio – Allegro vivace…………………………………………………………………12:09

II. Adagio…………………………………………………………………………………………..10:51

III. Allegro molto e vivace – Trio. Un poco meno allegro………………..6:05

IV. Allegro ma non troppo………………………………………………………………..6:57

Total running time: 35:22

My Rating:

Recording quality: 5 (I’ve always found that Warner Classics releases very fine recordings)

Overall musicianship: 5

CD liner notes: 5 (a nice, meaty booklet; lots of info in several languages)

How does this make me feel: 5

This is standard Daniel Barenboim. It is lush, well played, nicely conducted, and enjoyable.

I don’t feel this is quite a “Huzzah!” performance, though. It could be. But it’s not electrifying me. To borrow a lyric from Mr. Gershwin:

‘S wonderful! ‘S marvelous!

‘S awful nice! ‘S paradise!

But it’s almost too predictably good. Almost too dependable.

That shouldn’t count against it. But, somehow, it does. Just a little.

I’ll have to award this an Almost “Huzzah!” rating. It’s damn close. Perhaps it even is “Huzzah!” worthy. Yet, I tend to like more magic and surprise to my music.

But don’t let my quirks stop you. It really doesn’t get much better than this. Barenboim never disappoints. Neither does Warner Classics. This is collection worthy music.

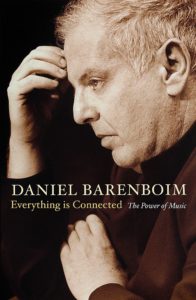

So are Maestro Barenboim’s books, especially Everything Is Connected: The Power of Music, his treatise on music, sound, silence, and what people have in common.

So are Maestro Barenboim’s books, especially Everything Is Connected: The Power of Music, his treatise on music, sound, silence, and what people have in common.

Here’s a sample:

Sound is not independent – it does not exist by itself, but has a permanent, constant and unavoidable relationship to silence. In this context the first note is not the beginning – it comes out of the silence that precedes it. If sound stands in relation to silence, what kind of relationship is it? Does sound dominate silence, or does silence dominate sound?

Let us examine the different possibilities presented by the beginning of sound. If there is total silence before the beginning, we start a piece of music that either interrupts the silence or evolves out of it.

The music does not begin with the move from the initial A to the F, but from the silence to the A. Or, in Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 109, one has the feeling that the music began earlier – it is as if one steps on to a train that is by now in motion. The music must already exist in the mind of the pianist, so that when he plays, he creates an impression that he joins what has been in existences, albeit not in the physical world. (pages 7-9)

Barenboim’s book is a loving and philosophical – yet, oddly, grounded and practical – tribute to music.